By: National Club Association

The run to the PGA’s FedEx Cup got underway this week with THE NORTHERN TRUST at The Ridgewood Country Club in Paramus, N.J. On the course, 125 players are trying to make history, and most of them probably don’t know that they are playing at a club that already has made history. The club, which was constructed in 1929, is listed on the National Register for Historic Places (NRHP).

For those of us who love golf, the game’s history has always been magical. We grew up on stories of Francis Ouimet, Bobby Jones, Ben Hogan, Sam Snead, Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, and countless others. And we grew to love them. But it’s just as important to remember the historic sites on which so many historic achievements were accomplished. Augusta, The Country Club in Brookline, Shinnecock, Baltusrol—and this weekend’s host, Ridgewood.

History and Significance

The Ridgewood Country Club was constructed in 1929, although Ridgewood’s origins trace back to 1890. Ridgewood, like Baltusrol, started with a humble golf offering—just a two-hole course in 1890, which was lengthened to nine-holes to accommodate the game’s rise in popularity. Eventually the club featured an 18-hole course, but Ridgewood decided that this 6,000-yard course was inadequate for championships and solicited the help of now famed Albert W. Tillinghast, who had built the dual Baltusrol courses just a few years prior. In 1929, Tillinghast designed Ridgewood’s 27-hole course.

Not to be outdone, another grandmaster architect, Clifford C. Wendehack, constructed the clubhouse. In 1928, Wendehack crafted the building in the “Norman” style, featuring its recognizable tower and porches. The style originated in France and England nearly a millennium before, but the similar landscape of northern New Jersey and northern France inspired the architect.

Process

According to David Clark, Ridgewood’s historian, Ridgewood is the only club that features a course and clubhouse built by grandmasters Tillinghast and Wendehack from scratch. The process to become an NRHP took three years, including process of applying to be listed on the New Jersey Register of Historic Places. Like Baltusrol, Ridgewood also hired a consulting firm to facilitate the application process.

Preservation

All 27 Ridgewood golf holes fall under the NRHP designation, as well as the clubhouse and several other buildings. It is important to note that its NRHP status is granted to each hole on the course, not the entire course itself. This means each of Ridgewood’s 27 holes is on the national register, and that if a hole changes too much from its original design, it may be removed from the NRHP.

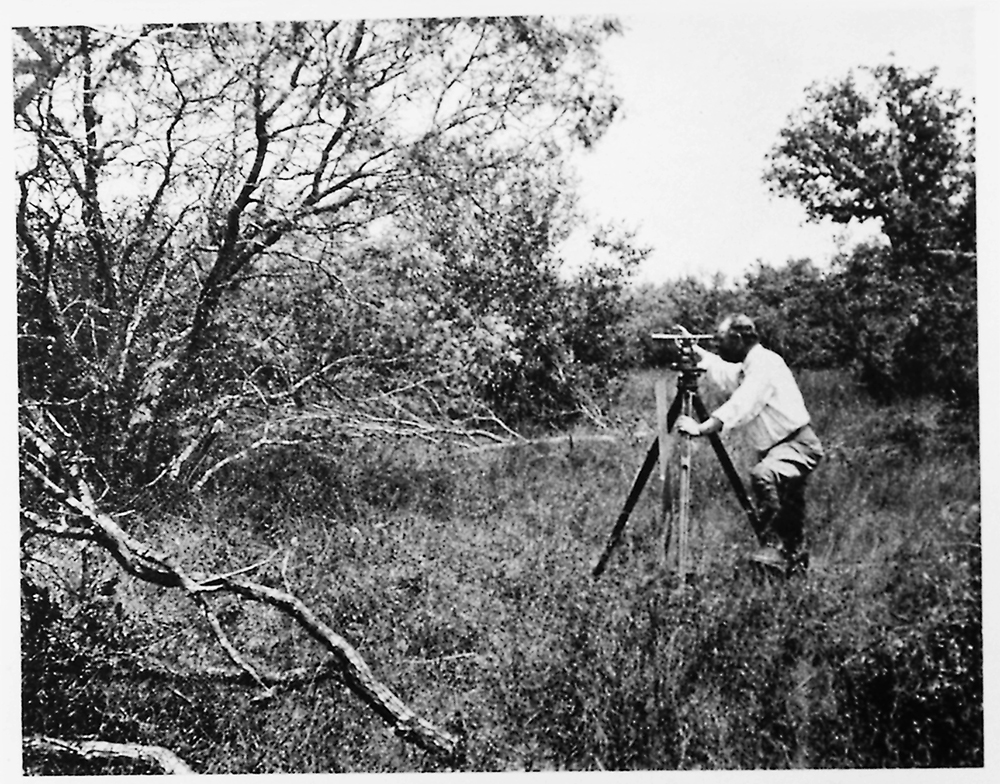

Clark notes that the golf holes are remarkably unchanged from Tillinghast’s original design, but preserving the course has taken meticulous effort. In accordance to Ridgewood’s master plan, Gil Hanse, golf course architect, was tasked to restore Tillinghast’s course to its original specifications. That project and other efforts since have examined all facets of the course to ensure its integrity, and included aerial images, other photos and even laser measurement.

Bunkers, greens, fairways and other parts of the course are all susceptible to change in design over time. Even with regular maintenance this is possible. Ironically, that maintenance, e.g., mowing, may be part of the reason these items change, pointed out Clark. Over time, as crews mow around greens, fairways and bunkers, those places often become smaller and lose their original geometric shapes.

Other changes are less deliberate and happen even more gradually. Clark mentions that trees and roughs have grown or have been cut down over time, changing the way the course is played. For example, Ridgewood has two holes where the fairways originally touched. Over time, a rough developed, separating the two fairways and the way the course was played. The master plan renovations corrected this and returned the fairways to their original form. Some additional changes also were made to the course. Like at Baltusrol, tee boxes were expanded to accommodate better equipment.

Preserving the Intent

The board plays a critical part in observing changes that could affect NRHP status, said Clark. A board that understands that courses are dynamic and thus ever-changing is critical to conducting routine checks to ensure that the course not only has its original layout, but also is still played in the same spirit as originally intended. Clark mentioned an example where apples trees were planted on one hole. This not only altered the way the hole was played but went against the style of play that Tillinghast originally intended. It forced many golfers to take pitch out shots, which the architect believed to be one of the most boring shots in the game.

The board also helped create Ridgewood’s master plan, which was critical in preserving the course and earning the club’s place on the national register. However, Clark noted that Tillinghast warned club boards that making small changes to the course would eventually make the course unrecognizable to its original design.